Exploring Evergreen Funds with a VC Investor Who Raised One

Open-ended or evergreen funds can be beneficial for venture capital investing due to the alignment, flexibility and transparency they bring between stakeholders. In a discussion with a GP who raised an open-ended VC fund, the potential of this asset class is explored.

This article was originally published on Toptal

Earlier in 2018, through Toptal, I worked with Rodrigo Sanchez Servitje from B37 Ventures on a project related to its open-ended VC fund. Such funds are still a relatively unknown and misunderstood type of funding vehicle, with a dearth of “in the trenches” information out there about how they operate. With this article, I am looking to correct that.

As someone who has raised and operated an open-ended VC fund, throughout the piece, I will refer to Rodrigo for invaluable insight regarding B37 Ventures’ experiences.

What Are Open-ended and Evergreen Funds?

In venture capital fundraising, as the adage goes, “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.” For years, funds have toed this line by raising capital through closed-ended vehicles. This refers to a management company raising a set amount from external investors via a limited partnership legal structure for a fixed number of years (typically ten). After this process, the doors close, money is put to work and, at the end date, the fund is wound up and repaid.

Despite investing in disruptive and innovative industries, the landscape of VC fund structures has largely remained unchanged.

The most obvious alternative would be the inverse of a closed-ended fund: an open-ended one. In these such funds, capital is invested directly into an LLC on an ongoing basis with no termination date. It is essentially investing preferred equity into a company: Investors buy units of a fund with a yield attached (the hurdle rate) and they can buy more, or sell, whenever they wish.

This type of fund is also liberally referred to as a permanent capital vehicle or evergreen fund. The ethos between the names is largely the same, in that it’s referring to structures with no end date or fixed capital quotas. A core distinction is that an evergreen fund can recycle returned capital while open-ended funds (like B37 Ventures) distribute to investors.

The Pros and Cons of Open-ended Funds

An open-ended fund can bring some interesting advantages to its stakeholders:

- Alignment: Managers can focus on capital appreciation without time barriers. Also meshes well with entrepreneurs looking to grow their business sustainably.

- Cleaner: Fund investors can take a long-term view without constantly needing to invest.

- Flexibility: More freedom to change an investment thesis and hold other types of investment.

- Transparency: One budget and set of management fees, instead of layers of costs that build up.

For B37, alignment was a key factor in choosing to go ahead. Servitje says, “Having an open-ended structure was the one that most aligned all the parties. Our target investors are corporations that have between $500 million and $20 billion of sales—for them to invest in VC, they’re not primarily interested in financial returns. They want strategic returns.

From a startup’s perspective, we can deliver them value by aggregating as many corporates and ‘scale’ as we can, in a useful way. The fund makes sense, as all of our investors are equally incentivized to evaluate, run tests, and be large customers on an ongoing basis for our portfolio. This should ultimately yield financial returns, which aligns us as a management team.”

There are drawbacks, though of course, if open-ended funds were perfect, then they would be more widespread:

- Illiquidity: For investors in open-ended VC funds, the promise of liquidity may be a moot point. Startups generally don’t pay out dividends and secondary fund markets are thin.

- Lumpy cash flows: Big exits at unexpected times can clean out a waterfall in one go.

- Valuation: The NAV of the fund must be absolutely transparent and consistent.

- Perception: Startups and co-investors may not have familiarity with how such funds work.

When Rodrigo faces questions about B37 being different and how it will function as a co-investor, he draws attention to the positive interventions that its fund has been able to make in its portfolio: “With any conversations with potential co-investors, we approach it with: ‘This is our track record with our portfolio companies.’ We don’t talk about the fund makeup. Instead, we talk about how much time we spend within corporates, finding out about their needs, then finding startups that can grow within these economies. We’re always happy to show examples of our results, case studies of opportunities we saw, and what we did for our startups in terms of bringing in warm sales leads within 12 months of investing.”

How Many Evergreen Venture Capital Funds Exist?

The number of evergreen VC funds is estimated to be around the 200 mark, with approximately 100 coming into existence inside the past 20 years (Pitchbook). To put into context how niche these structures are in VC, there are over 10,000 investors globally classed as “Venture Capital” funds.

As a caveat to this, the “real” number of evergreens is likely higher than 200, because this manner of investing is widespread amongst angels, family offices, and corporate venture units. Oftentimes, these funds sit under the umbrella of an organization and are not disclosed through usual data channels.

Of the 92 evergreen VC managers that initiated since 1998, almost three quarters are based in the USA or UK. This is unsurprising, given that both countries have the most fluid capital markets and are seen as central hubs of entrepreneurship within their territories.

Again, no surprises that software is the most popular investment vertical for evergreen VC funds, but what is interesting is the popularity of life sciences. This would appear to be a sector that complements well with an evergreen mentality, due to the long testing and approval phases undertaken by new technologies in the industry.

How Do Returns Compare to Closed-ended Funds?

When comparing evergreen fund performance to an overall VC benchmark (encompassing all types of funds), returns are largely similar from a “Total value to paid in” (TVPI) perspective. As we know, VC returns have irregular returns distributions and as such, a benchmark does not paint a complete picture. Nevertheless, despite evergreens and closed-ended funds having different mechanics, it does not seem to affect their TVPI returns (Pitchbook).

Where this returns analysis gets interesting is when TVPI is deconstructed into its components of “Residual value to paid in” (RVPI) and “Distributed to paid in” (DPI). Wherein the characteristics of evergreens really become apparent, they have low DPI but high RVPI compared to more closely aligned metrics for the VC benchmark.

This demonstrates a validation of the long-term approach that evergreen funds take, showing that such a tactic can be more value accretive (RVPI), but at the sacrifice of quicker distributions (DPI).

Mechanics of Raising and Operating an Open-Ended VC Fund

Fundraising Is Less Daunting If It’s Carefully Planned

There must be a compelling reason to raise an evergreen or open-ended fund beyond just because it’s something different. It is vital to align it with your own motivations and also to ensure that it adds value to investors and the businesses that you plan to invest in.

An open-ended structure must complement your investing environment or views. For example, you:

- Have a strong belief in “sum is greater than the parts” investing and wish to leverage a position as a timing-agnostic investor to foster this in a portfolio.

- Have a view that an investment philosophy can be distilled into an inter-generational firm that can continue on without you one day.

- Are in an emerging market country where exit waits are longer.

For Rodrigo and B37, such a structure resonated with them due to their thesis that large corporates and startups have mutual interests: “We think that we have two sets of customers: startups and investors. Our strategy is adding as much value to both. We don’t think of ourselves as a fund, more as a platform—startups and large corporates exchanging innovation and scale. Most of our investors are large corporations with huge scale around the world, but in need of innovation. The best startups are the opposite—innovative, but not global, they need scale. We try to put those two together through investing.”

In terms of identifying investors, for seasoned managers that wish to simply change their funding vehicle type, the process will come down to communicating the reasons why. For first-time GPs or unproven managers, it will naturally be a more complicated process—but one that can be assisted by marrying the needs of potential LPs with the virtues of your fund. Corporates and endowments, for example, are LP types that like to lock capital away long-term, with a yield target in mind. B37 Ventures looks to tackle investors’ pain points with its pitch:

“Our target investors are large corporates and family offices that don’t need to return capital quickly.

“When talking with them about making $5-20 million investments, their argument is: ‘If I give you $5 million and you earn me a 10/20x return, you’re not really solving a need that I have. I don’t have a need to make return, I have a need to manage capital. Yes, you’re giving me a great return, but you’re not resolving the problem of how I manage money.

“A good investment is when you invest and then forget about it, knowing that it’s safe and increasing in value.”

One factor to be aware of when fundraising is getting the legals understood and streamlined. Despite open-ended funds having a potentially cleaner structure, with less interconnected entities to deal with, it can be difficult for the VC to find a lawyer that has familiarity and a track record with them. Fortunately, Rodrigo noted that the structure is easier for investors to digest and work with: “It is easier on the investor side. In closed-ended LP agreements, there can be different rules for different investors, across different funds. Our aim is to make it easy for new investors, as if they were buying stock on TD Ameritrade. There’s nothing to negotiate, just buying units.”

Day-to-day Operations Have Small Differences

Budgeting does require some slight alterations, in that unlike the % of AUM model, an open-ended fund will agree upon a budget with its investors. Rodrigo noted that this is not very problematic, as approximately 70% of a VC fund’s costs are “relatively fixed.” When I asked him if he needed to adopt a different “mentality” when investing open-endedly, his view was: “Not in our case, but we do that intentionally. The best innovations will have the best financial returns. We keep ourselves in a space where we operate and make decisions as if we were a ‘normal’ VC fund because, like them, we are compensated on financial performance. We want [co-investors] to be aware of this and our intention is to keep it that way.”

With evergreen funds having no end date and with the flexibility of being able to top them up with more capital, planning investment timescales can seem endless. As with any fund, retaining dry powder for follow-ons and opportunistic plays is crucial, but exits add another dimension.

A common misconception regarding exits in open-ended funds is that they can recycle capital. That is in theory possible, hence the term evergreen, but it can be counterintuitive towards aligning the interests of the manager with the LPs. If there are no distributions, there are no chances to realize profits. Clawback provisions are not common in open-ended funds and so, recycling capital can make it hard to retain quality investment staff, who will be perpetually waiting for performance-related compensation.

Instead, the fund manager must look to tie up exits with future fundraising, almost as if LPs are in cohorts, bookended between exits. An exit represents a soft reset where capital can be returned and potentially reinvested by exited investors. This was a focus of the work that I did with B37, to ensure that fundraising is planned for optimal timing and with the best interests of current investors in mind.

To visualize the cash flows of an evergreen fund, the chart below plots an example of the timing of cash flows by activity.

Valuation and Buy-Ins: Complement NAV Metrics with Flexibility

The NAV of the fund is of high importance, both in terms of allowing current investors to track their marks and for new investors assessing whether to buy into the fund. For that, providing regular, transparent, and consistent valuations of the portfolio is paramount. For B37, valuation is always the major talking point with investors: “We’re always fundraising—we do raises once a year. The major question is always how do we determine the price for new investors that come in, and who approves it. Everyone likes the structure, understands why it’s there and its advantages. At the end of the day, for our model, the price per share is the ultimate equalizer than makes it fair for everyone.”

An open-ended fund structure also brings an advantage that LLC terms can be altered as time progresses. This is particularly useful for managing new fund buy-ins, because it allows for subjective valuation elements to be inserted. NAV is a great quantitative metric, but on its own is not a complete tool for assessing fund value for new investors, such as in these areas:

1. Network Effects. The composition of an investor base in a fund is a leading indicator towards its future success and thus, sends signalling properties to the market. New investors arriving with a combination of pedigree and absolute investment dollars will benefit the existing portfolio and investor base. This is especially relevant for funds such as B37, which actively involve LPs in their investments to explore commercial collaboration opportunities. The new investor also benefits from having a “second mover advantage”, through being able to pass into the slipstream of an established brand, operational and due-diligence practices

2. Financial Justice. NAV is useful for secondary transactions, as it’s a zero-sum game: no new capital is being invested. But for new investors, whose capital will not physically be deployed in existing investments, it’s only fair to incumbents that they do not participate in their gains. This can be achieved by altering the LLC to include designated investment groups for new capital that arrives within certain timescales. Hedge funds deploy similar strategies with side pocket investments that are carved out from the main fund.

Rodrigo notes that this model may be fairer on LPs overall, compared to closed-ended models, where investors buy into funds at the same price despite the GP undergoing a constant evolution of their own skills as fund managers: “When I think about the B37 pipeline, we have been in the market for five years; we’re making better investments now and will most likely be even better in the future. In a ‘series of funds’ model, would investors in Fund One be taking on larger risk and paying for our development as managers? Most likely, they would. How do you level that playing field? It’s cleaner to keep it all in one structure.”

Rodrigo also noted how LP redemptions are not really possible in an open-ended VC because the underlying assets are illiquid. In a private equity fund structure, concessions can be given of offering up a percentage of the NAV for pro-rata distribution. For venture capital, B37 sees improved secondary markets as a step towards offering this benefit to investors: “There might come a day where some or all of our supply comes from secondaries. We wanted to leave that door open to see how markets change and evolve. The VC world is growing, and more and more are taking interest in it. There could be the potential for redemptions in the future.”

There Are a Number of Ways to Manage Distributions

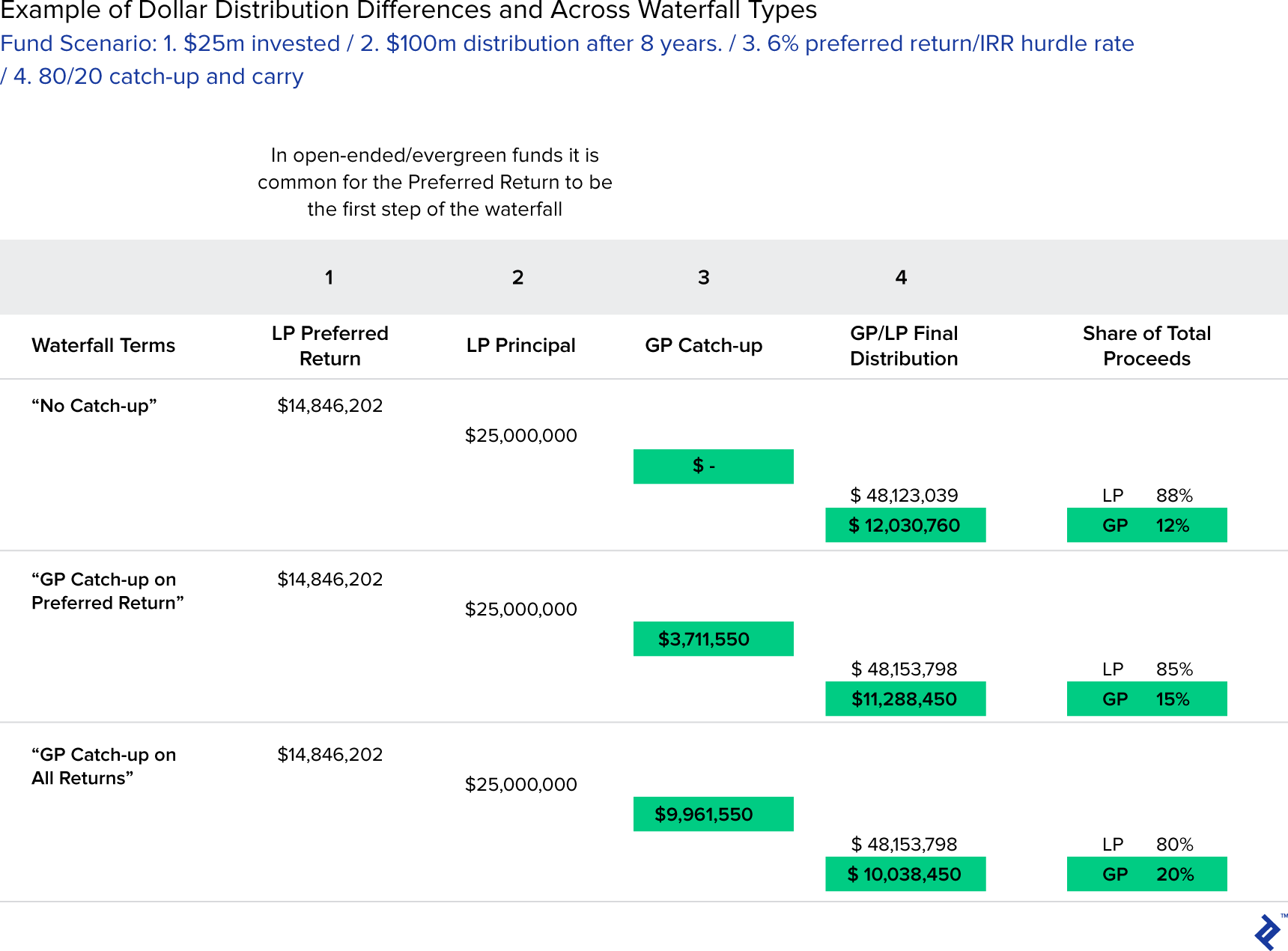

In typical fund waterfalls, the following order exists for distributing returns:

- LP principal

- LP hurdle rates (a minimum IRR return for the fund)

- GP catch-up (a percentage of the LP hurdle rate)

- Final profit share (A split of remaining funds, typically 20% going to GPs)

With evergreen funds, one difference is that the preferred return (or “interest”/”yield”) component is typically paid first, before principal. Because an evergreen could, in theory, continue perpetually, it’s critical to reward investors properly for the time value of their money. If principal were cleared before yield, investors may find themselves earning a lower return in future years (from the reduced principal base) despite not yet receiving material gains from the fund. Rodrigo is sanguine about this but again brings it back toward marrying interests with investors: “The preferred return is the ultimate way of making it fair—if we can’t beat the market, then we don’t get carry. Of course, we want to be as good as the market. Principal or yield first? I don’t have a preference between one or the other. It’s what makes sense for your investors and makes it fair.”

From a waterfall perspective, if preferred returns are paid out first, it may take longer for the waterfall to cascade down in its entirety. Depending on the catch-up terms chosen, the end results can vary in terms of the proportionate split of total profits.

Unlike evergreen private equity or real estate funds, there are rarely interim cash flows in venture capital between investment and exit. This can present distribution scenarios where there is nothing for a long period, followed by a huge exit that can instantly wash a waterfall down to its final step.

Large realized exits are, of course, cause for celebration, but the GP must be cognizant to their timings because the clearing of the cap table and profit taking may then require a recapitalization of the fund.

Growing the Firm and Planning for the Future

In an open-ended fund, there is the potential to grow an intergenerational investment business. Many closed-ended funds are inherently tied to the star manager, who takes LPs with them when they leave, or the management company shuts down when they retire.

With a stable capital base and with success behind it, an open-ended fund can grow and further its reach. Rodrigo notes this as one of B37’s goals going forward: “We do think that we can grow AUM significantly under our current structure. Our plan is to keep pushing to get more companies from different parts of the world into our network effects. Most of our investors are headquartered in LATAM, but we do have conversations with corporates elsewhere, especially in Europe and the Middle East. It will enrich our value proposition by bringing in more diverse corporates.”

Because of the flexibility that an evergreen fund structure affords, there can be the temptation to experiment with bolt-on businesses, like accelerators or company builders. Rodrigo errs toward caution in pursuing such endeavors because of the potential for conflicts of interest with existing portfolio investments.

What makes evergreen funds a topical discussion for this age is the emergence of token-based investment funds attached to blockchains, because they are in a sense, evergreen investment vehicles. Proponents of these funds say that investors have more liquidity options through the token being listed on crypto exchanges and investors being free to make markets there. Yet, as with any asset, OTC, or exchange listed, there is only liquidity if there are pools of willing buyers and sellers.

Rodrigo views any innovation and challenging of norms as good, but such an arrangement wouldn’t make any difference to B37’s fundamental goal: “It’s interesting and I’m glad some people are exploring and debugging it. But I don’t think we would have to go to that length; we just want to find the best companies and invest in them.”

I hope that this article can provide some insight into this fascinating niche of investment vehicles. As the analysis and input from Rodrigo shows, open-ended and evergreen funds may not be everything for everyone, but for some, it could be a flexible and rewarding way of putting money to work.