Fintech and Banks: How Can the Banking Industry Respond to the Threat of Disruption?

The popular fintech narrative is startups using technology to disrupt incumbent banks. How can banks respond better to the “fintech vs banks” movement?

This article was originally published on Toptal

Banks Can Play the Fintech Game Too

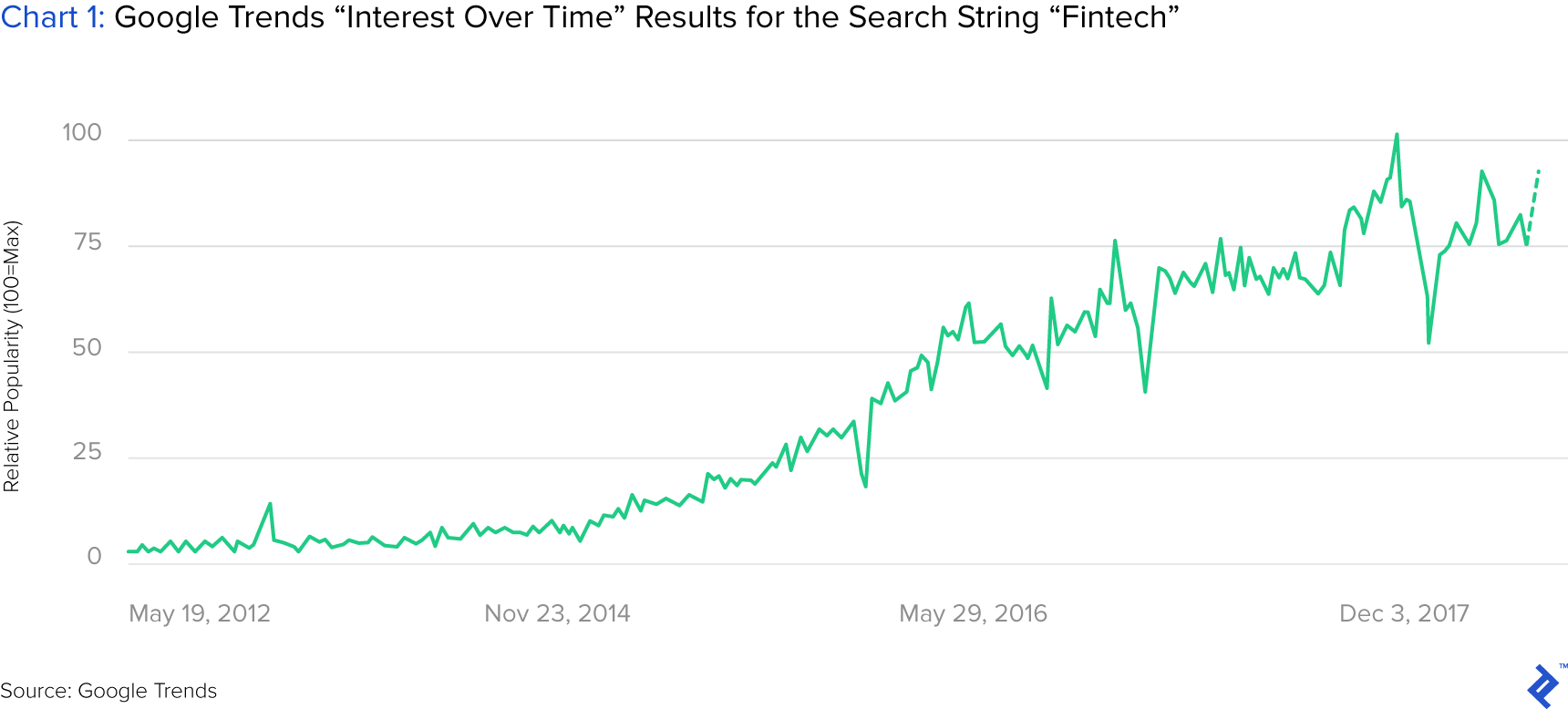

Fintech, shortened from financial technology, is assumed to be a modern movement, yet the use of technology to assist financial services is by no means a recent phenomenon. Financial services is an industry that introduced credit cards in the 1950s, internet banking in the 1990s and since the turn of the millennium, contactless payment technology. Yet, fintech’s place in the public conscience has really taken off in the past three years:

The takeoff of this term has come from startups—actors not within the inner circle of financial services, taking a more prominent role within the ecosystem. Three core trends have led to this emergence:

- Technology: Financial services traditionally was an industry that required fixed assets (for example, branches) to scale, acting as a barrier to entry to newcomers. Technological advancements now allow upstarts to run complex operations virtually. For example, neobanks operate purely on technological infrastructure. UK-based Revolut has amassed 1.5 million customers (of which 350,000 are active daily) without any kind of live customer-facing function.

- Customers: In the aftermath of the Financial Crisis of 2008 and various other scandals, customers are demanding more from their banking services. Technology now empowers consumers to scrutinize their providers more heavily and upstarts are harnessing it to provide cleaner and more effective customer service, free from the shackles of legacy technology.

- Regulation: Increased regulatory oversight on banks post-2008 is estimated to cost the six largest US institutions ~$70 billion per year. Citigroup alone employs 30,000 within its compliance division. Aside from complying with regulations, restrictions on lending have both increased the fully-loaded borrowing costs to consumers and diminished banks’ ability to offer it. This has allowed startups who, because they are not de facto banks (and thus under less oversight), step in and offer compelling alternatives.

The narrative that the fintech landscape suggests is that startups are using technology to disrupt incumbent banks. Yet, there is no reason to suggest that banks are facing their own Kodak or Blockbuster Video moment. They still remain widely used, profitable, and cash-rich businesses. What this article will address, though, is how they can respond better to this “fintech vs banks” movement as, in my opinion, their response so far has been suboptimal.

Fintech 2.0

So far, fintech startups have not looked at the widespread disruption of all financial services. McKinsey analysis of a sample of startup data shows that 62% of startups are tackling the retail banking segment, with only 11% focused on large corporate banking offerings. Payments is the most popular area to usurp and lending is the most lucrative area of banking by revenue being targeted:

The response by banks right now to fintech disruption is critical due to the current stage of the nascent industry’s development. Fintech startups are broadly focused on the concept of unbundling banks, offering one type of product/service and concentrating on doing it VERY well.

Innovation thus far has been largely driven on the front-end within these specialized offerings, mainly through improving customer-facing facets of financial services. Some examples of how this is being done are:

- Better service: A traditional bank largely ties a customer in by offering them a range of services that make them sticky, through increased switching costs. Without this luxury, specialized fintech companies follow a mantra of earning trust through better customer service and referral-based client acquisition. 90% of fintech companies cite enhanced customer experience as key to their competitive advantage.

- Better branding: With employees from non-traditional banking backgrounds adding an unbiased perspective, the fintech industry is refreshing the branding of the legacy services that it is trying to upend. Modern marketing tools like gamification are making mundane tasks like budgeting appear exciting and more palatable to consumers.

- Cheaper prices: Having a leaner virtual operation, more flexibility through not being regulated as a deposit-gathering institution, and cash from venture capital allows fintech startups to attract customers with competitive pricing.

FINTECH IN THE BACK-END OF FINANCIAL SERVICES

Bringing in new customers will allow a fintech firm to validate its product, receive feedback, and buy time in lieu of the second paradigm: improving the back-end of financial services. The back-end of finance, the “rails” of the industry, consists of the established infrastructure that banks use to interact and transact with each other, such as clearing (NSCC), payment (ACH), and messaging (SWIFT) systems. Widespread movements to disrupt these norms have not emerged, although the potential of new technological applications such as blockchain technology within these areas is enormous. A significant event did occur here in 2017, when ClearBank became the first new clearing bank to open in the UK in for 250 years. This will give it license to build and offer new, modern rails solutions to stakeholders of the financial services world.

Behind the better customer service and beautiful apps, the back-end of a fintech startup largely follows the same processes of a bank. When you make a payment through Venmo, get a loan through SoFi, or invest in Betterment, you are not going through a “new” financial system. These firms rent and utilize the same legacy infrastructure that banks use. They work wonders to make the system appear better to consumers, papering over cracks and bureacracy, sometimes with audacious claims like Transferwise’s peer-to-peer FX model—an almost impossible feat to really achieve in the mismatched world of cross-border payments. Startups’ front-end driven business model presents two existential threats to its fintech ecosystem:

- Their costs to use the rails will always be higher than the incumbents, as they are renting them.

- Their lights can be turned off at a whim as they are conduit middlemen within the service.

For that, until fintech can move to fintech 2.0 and create its own rails, it will have a huge strategic risk and banks will have time to respond. To ascend within the financial services industry, fintech startups will need to forge a new technologically-led back-end for the industry. A continuation of their tech-led front-end and a rented process-led back-end, designed generations ago, will ultimately result in sustained margin compression and high operational risks.

Creating new banking back-end processes will be difficult, due to format adoption consensus topics that will arise (think Blu-ray and HD-DVD) and involvement that regulators will play. But reaching this and having a seat at the table will at least allow startups to operate on a level playing field and mitigate the existential threats that hang over them. Until that point, they may remain on the fringe, merely papering over the cracks of a creaking financial services system.

In light of the current situation of fintech businesses, I will now switch the attention to banks and how they can respond to fintech technology in a better way. Their responses so far have erred more towards Kodak than Koninklijke Philips, which sold its music business in the 1990s in anticipation of the MP3 revolution.

1. Fight or Flight

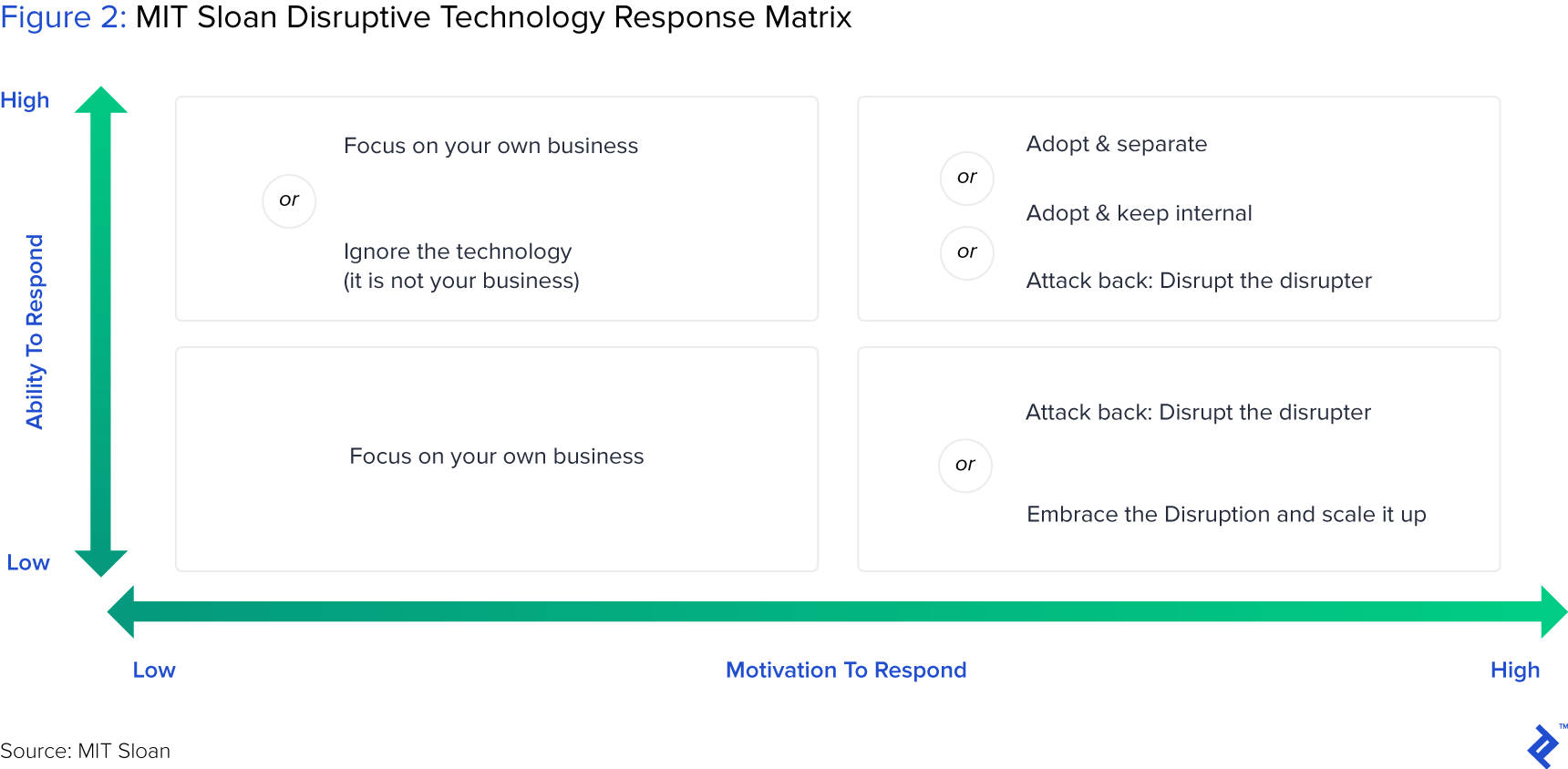

The figure below shows a framework by MIT Sloan that categorizes responses to disruptive innovation, two factors affect the incumbent’s response, motivation, and ability:

Based on current actions, banks sit in the top left quadrant. They have displayed low motivation despite their high ability to respond to fintech. They have the wealth and staff numbers to tackle the disruptive potential of fintech startups, but their responses have been either dismissive or passive. Regarding the former, not a week goes by without a financial services chief scoffing at Bitcoin or robo investing. In terms of being passive, banks have mostly engaged with fintech through soft-touch accelerators or direct equity investing which, in its purity, is a form of outsourced innovation.

In my view, if a bank really wants to respond to the fintech movement constructively, they need to increase their motivation and either fight or flight.

Fight

By fight, I am referring to ripping up the norms of the industry and trying something completely different. The rails of banking are old and confusing; manual and institutionalized processes that were built up in the pre-internet age have formed around them and become the status quo. These have increased the prices and bureaucracy that consumers face. Even now, only 7% of credit products in banks can be handled digitally from end to end.

One advantage that banks hold over fintech startups is that they know the keys to these rails through historical processs knowledge. Improving them will provide banks with efficiency gains that can be passed through to consumers via better pricing. A better service will also win transaction rents from fintech startups, who will use the service. Considering that upstarts are following a mentality of “unbundling” the bank, it’s reasonable to suggest that they would be content to rent a newer form of infrastructure, so long as it’s malleable, transparent, fast and provides good value.

With their vast financial resources and technological prowess, this is achievable for banks. Although it’s a risky move, firstly for the cost and secondly for the “prisoner’s dilemma” aspect of going against peers and trying something different. If they do not participate in this change, someone else will and the industry will eventually move to new rails.

Flight

Before they went full-service and became conglomerates with investment, commercial and retail arms, banks were good at what they did. Sound credit practices grew from branch managers granting mortgages to local customers that they knew and saw at regular occurrences.

A contrarian response to fintech, but one that is worth consideration, is that banks acknowledge the inevitability of the unbundling of financial services and retreat back to their roots—using their infrastructure to be “enablers” of financial services, such as custodians for deposits, and also applying their scale to revert to the form of human interaction which is being shunned by fintech. One example of this focus is Metro Bank, a new UK bank that opened in 2010 with a simple portfolio of services and the first new bank in 100 years to offer branch infrastructure. It has since IPOed and opened 41 branches.

Retreating from the empire-building of conglomerate banking is a hard pill to swallow. If the unbundling of financial services does succeed, conglomerates will represent bloated generalists in the system. Spinning off consumer banks and the return of investment bankers back to the boutique model will afford each entity the time to focus on what they do best and survive through specialization.

2. Reasses the Goals of Investing in Fintech Startups

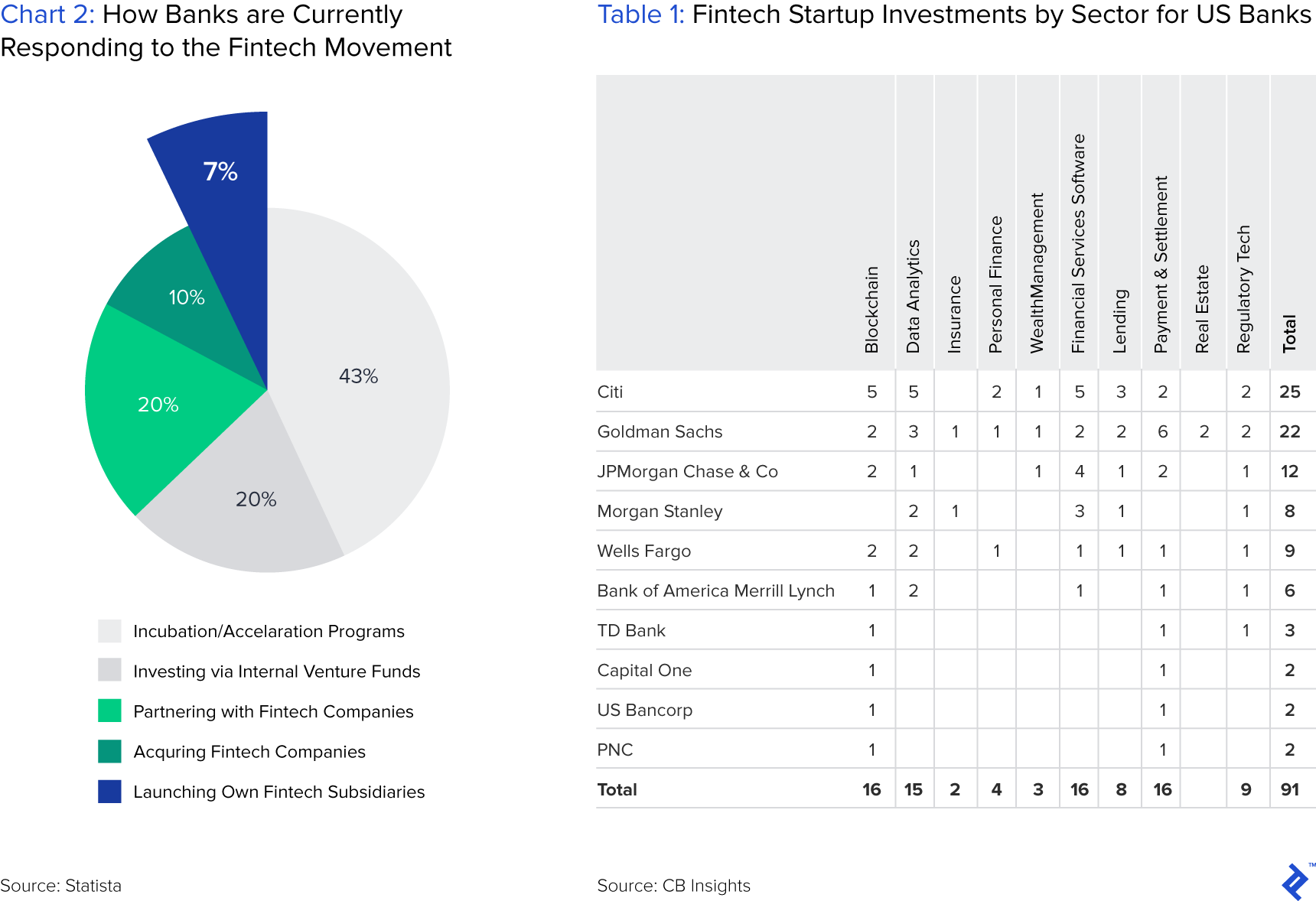

I referred earlier to the outsourced innovation aspect of financial services’ current response to fintech; 63% of them have set up accelerators or startup venture funds. US banks alone have invested a staggering $3.6 billion in 56 different fintech startups. Conversely, only 7% of banks have done the hardest job of setting up their own fintech R&D offshoot to create proprietary solutions:

Some could call investing in the enemy a Machiavellian touch of genius, but it could also be called overly-passive. For all the wealth and resources that banks have, to be relying on fledgling startups to drive the innovation of their industry strikes me as misguided. Likewise, accelerators are easy to set up, but as data shows, have varying degrees of success. Despite the PR karma and confirmation bias of “being involved” through running a fintech accelerator, operating it with an internally-lead syllabus could skew the insight the startups receive, compared to an independent program.

More Collaborative Equity Investing in Fintech Startups

**The end-game of banks investing in startups is also confusing. If it comes out well, there will be a one-off financial windfall, but presumably one would also infer that the disruption faced by the bank has now scaled. Acquiring the invested companies also results in integration difficulties and the zero-sum game of cannibalizing existing offerings via the startups’ own. The incentive to be involved and keep a finger on the pulse also runs the gambit of alienating other investors and distracting the founders’ unfettered direction.

Taking equity stakes in startups should be more of a collaborative exercise for banks. One of the core value-adds that a corporate investor provides, over say traditional VCs, is that they have a sandbox of clients and activities that are potential customers of the startup. Instead of investing with a view to perhaps aquire the startup at a later date and hoard it for itself, bank investors should open up their own client roster to the startup. Such iterative tests will allow for the startup to validate itself and for the bank to provide a value differentiator to clients, while demonstrating internally what industry innovation really looks like.

Banks should also be more innovative with their capital and start upshot fintech ventures, labs completely separate from the main operation. This could be in the form of spun off independent groups, capitalized with equity and with no internal transfer pricing or involvement from the parent, staffed either with capable internal staff or external hires who receive “founding stock”. As the only shareholder, the banks will have control through the board, which can correctly steer the company through independent directors and the founding team’s motivation. Marcus by Goldman Sachs shows an interesting application of an “independent” offshoot formed inside a big bank, in the space of two years it has collected $20bn of deposits and underwritten $3bn of loans and is now expanding internationally.

3. Change the Cost Culture of Cross-Subsidization

A focal moment in banking is the yearly budgeting process, in terms of defining revenue targets and, equally, costs that will be apportioned to divisions. Everything from rent to the flowers in reception needs to be shared out. While egalitarian cost accounting methods bring transparency to this process, continually rising costs place more pressure on short-term goals of reaching yearly targets at the expense of long-term planning. Cost increases arrive all the time—Brexit alone is estimated to increase bank costs by 4%.

Cross-subsidization is evident in products too, whereby some products have a higher return on investment than others for strategic reasons. There is a reason why student bank accounts come with large overdrafts and free concert tickets—it’s because banks want to attract new customers who, ten years down the line, will be purchasing houses with lucrative long-term mortgages.

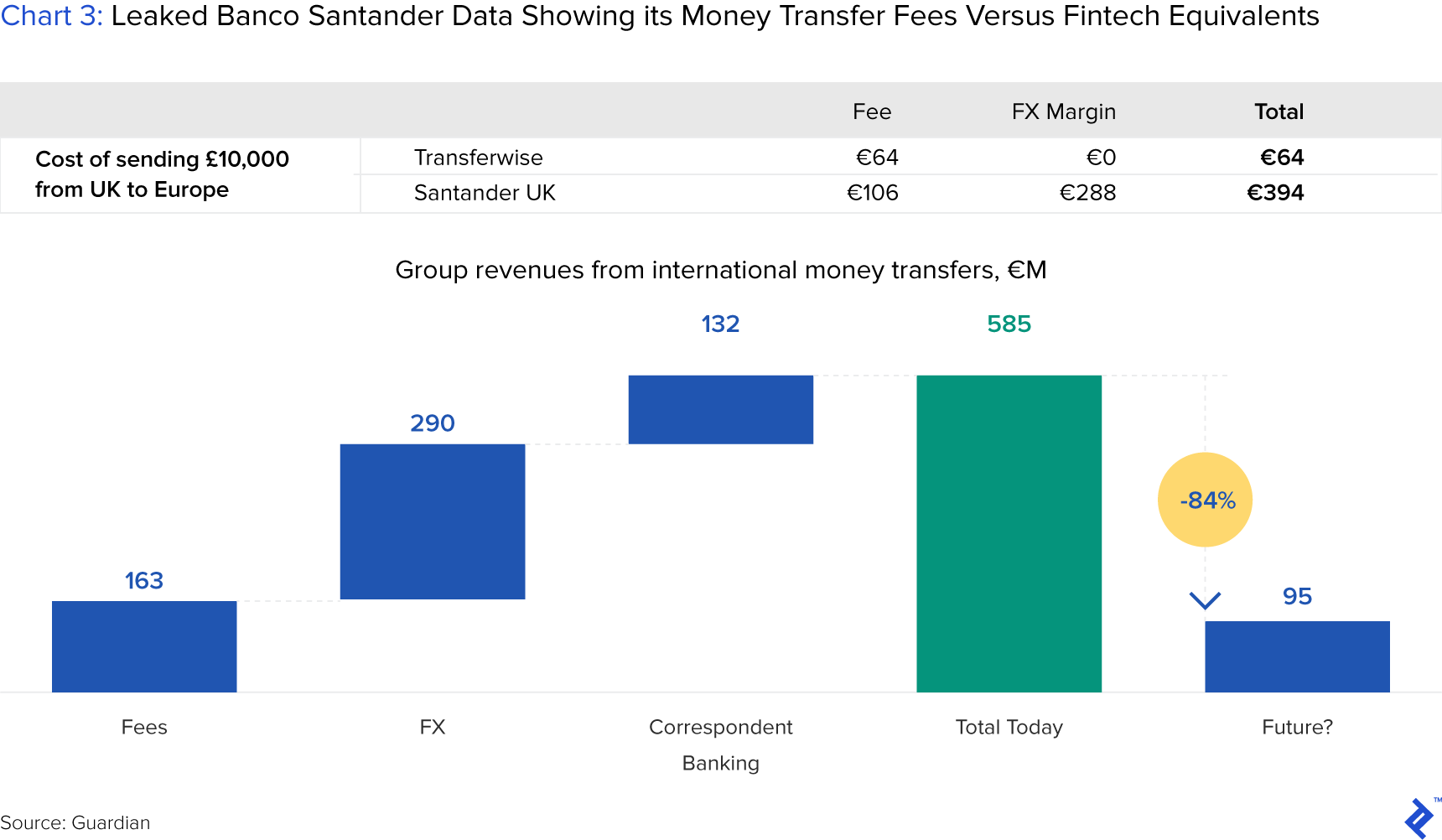

Banks operate in vertical silos where each team performs specific functions and, if a deal requires multiple services, multiple teams are involved. Because each team has its own cost structures and profit targets, they each require their “piece of the pie”. A 2017 leak received by the Guardian of a Banco Santander report demonstrates this for money transfer, where three teams in Santander combined to earn €585 million in annual revenue from the service. When compared to the transparent and cheaper fees from Transferwise, it shows a stark contrast:

For large banking operations, you would expect cost economies of scale to kick in and synergies to coexist between teams, I would argue that this is not the case. The nuanced nature of banking means that uniform rollouts of bank-wide programs, such as the use of specific software, or even graduate training programs that take a “one size fits all” approach, may not be suitable for teams in their specific needs. Likewise, the siloed nature of budgets and targets means that synergies that sound good on paper often don’t transpire in reality.

Resolving this issue is complex but critical towards empowering bank teams to think with a long-term mentality, a luxury provided to fintech startups via venture financing. Because banking teams have one-year budgets with high-cost hurdles, they are often fighting fires to reach the targets and any longer-term planning is a secondary concern.

To rectify this, banks must look at their budgeting and cost-sharing process and take a more ruthless approach over an egalitarian one. True core functions, such as treasury, must remain shared by all teams, but other central functions should be opt-in/out as to whether specific revenue-generating teams cover a share of their costs. Instead of pro-rata sharing of costs based on a share of notional traded or headcount, costs should also be allocated taking into account the effort and complexity required for certain activities. Zero-based budgeting would also prevent cost-creep and wastage from the age-old process of superfluous spending in the final months of the year to ensure that budgets aren’t reduced.

Longer term budgeting would also reward teams for sustained growth and innovation should be encouraged though allowing teams to allocate their own funding to R&D fintech initiatives.

4. Align Compensation to Important Emerging Skill Areas

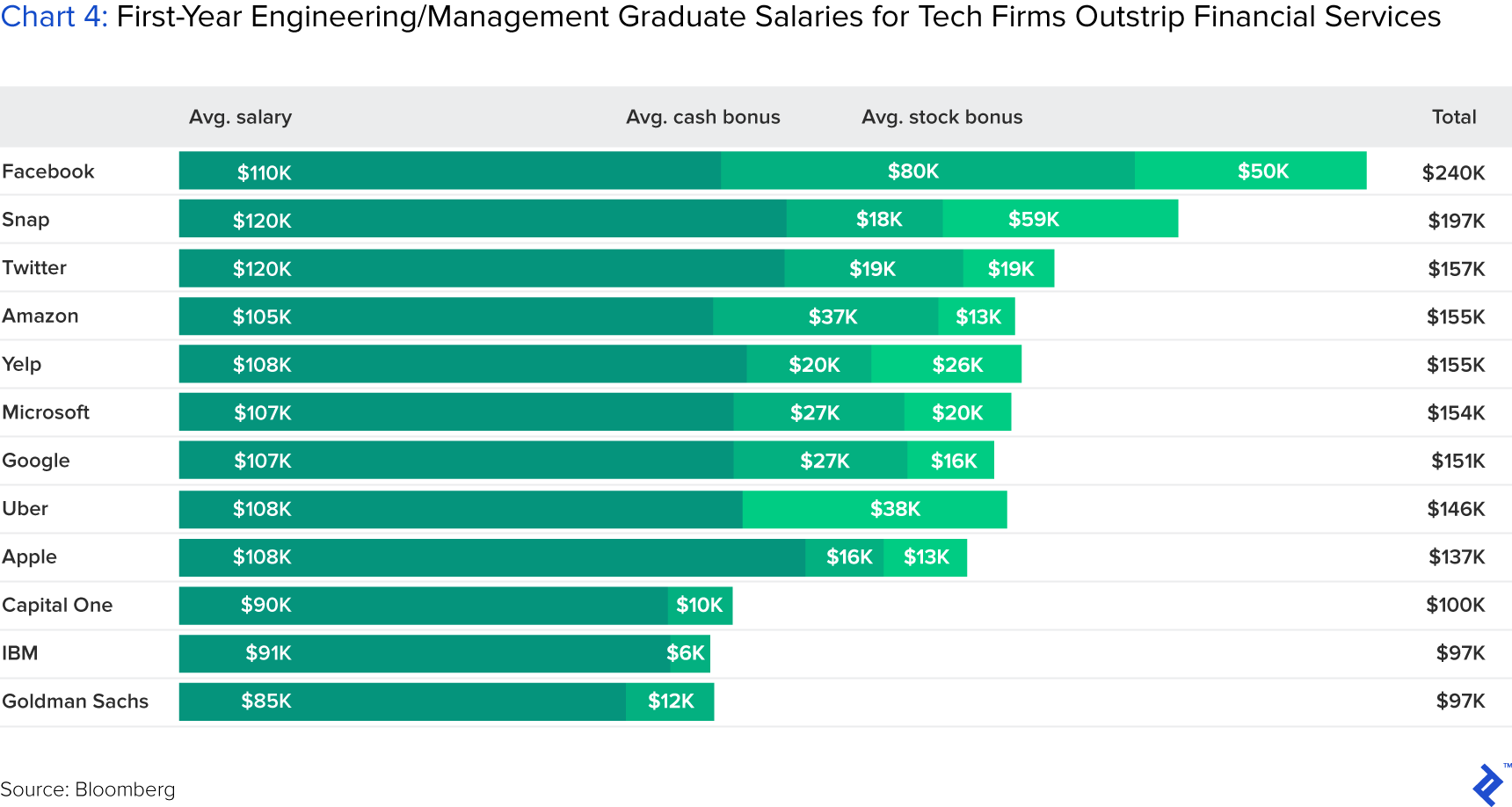

In 2007, almost 40% of MBA graduates from top US schools were entering the finance industry. These numbers have now shrunk to below 30% and the tech industry is poised to become the most popular sectoral choice. Various banking scandals have contributed to banks losing their veneer and, despite still being a very well-paid industry, some of the larger technology companies now pay more to graduates:

Stock options are regularly offered within banking compensation, but it can be argued that stock options in the tech industry offer greater potential upside. For example, Amazon has a price-earnings ratio of 256, 11 times higher than that of Goldman Sachs.

Targeted wage increases and a more compelling bonus plan could quickly rectify this. In addition, decentralized teams and longer-term budgeting may help to stem the qualitative reasons for talented staff leaving for the intellectual rigours of a tech company.

Away from headline figures of graduates and star traders, banks also need to look at how the importance of certain staff roles has shifted inside the current environment. As mentioned, technology has always played a key role in banking and banks have very competent resources in this regard. Yet, in a tech company, coding and development skills are lauded and staff with these roles play pivotal parts in business design. Banks, on the other hand, often see technology as a horizontal operation, there to support all teams agnostically. These teams also tend to not have physical proximity with revenue generating functions, seen from the popularity of hubs in offshore locations, from Budapest to Bangalore.

To foster innovation better, revenue generating teams should integrate critical support functions into their front-office operation. Core banking is essentially a commodity service; what separates the wheat from the chaff is the strength of qualitative aspects (deal-making ability, reputation, and connections) and technology (speed of execution, software employed, and settlement reliability). Rewarding those who assist the latter with more variable compensation tied to team performance will incentivize those employees to devise innovative changes and also increase the attraction of remaining in banking.

What Will the Future of Banking Look Like?

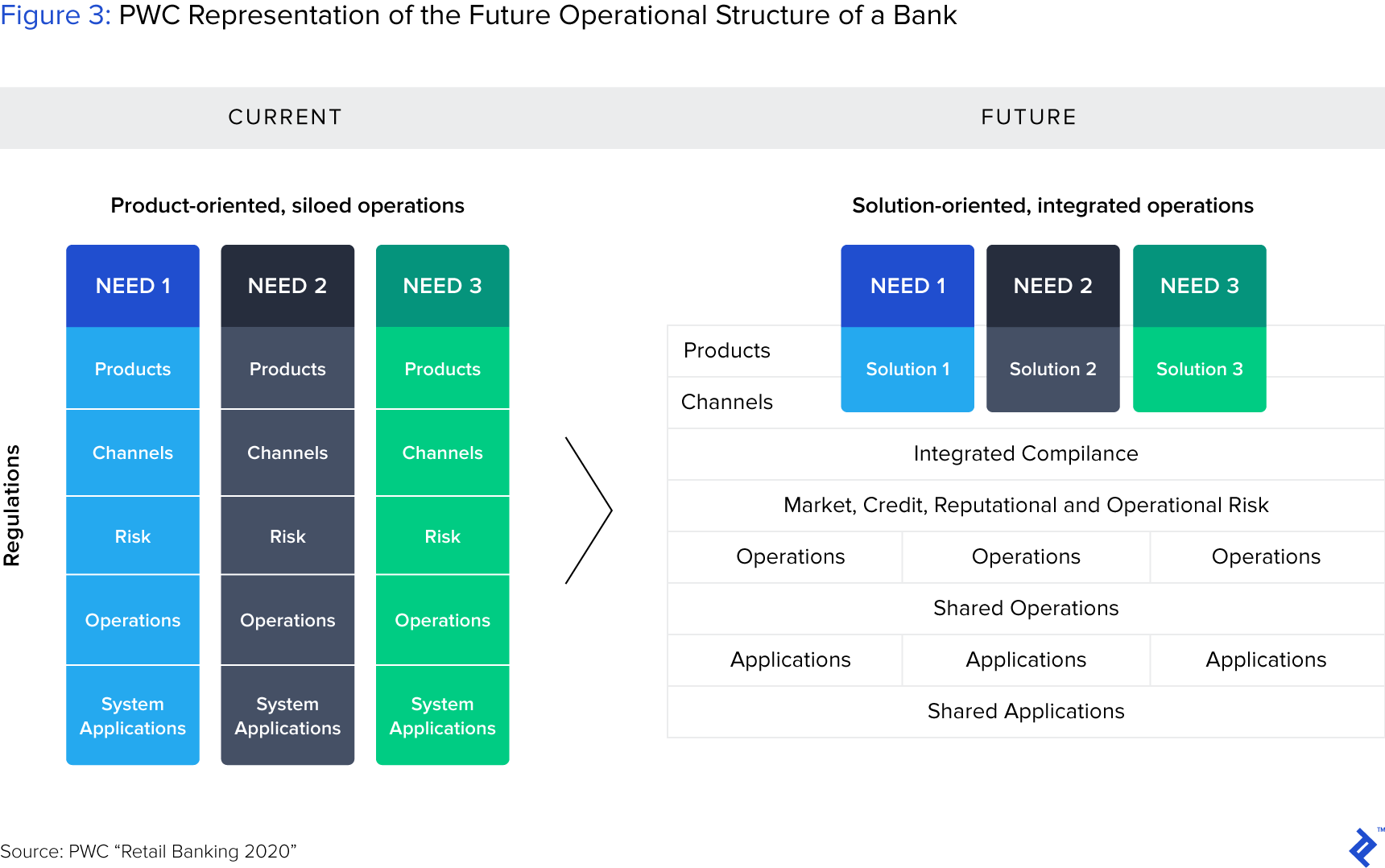

The movement of unbundling the bank, which follows the ethos of using division of labor to specialize in doing certain tasks well, is a lesson for the future for incumbent banks. Full-service banks are siloed machines that function by performing set tasks within divided units. Over the years, these have added up to be both rigid and expensive to the end user, which has inspired the fintech revolution to innovate around creating solutions to needs. PWC illustrates the mentality change needed by banks well through the following infographic:

In my opinion, in the future, there will be two types of large banks: One will be simple but effective traditional banking units that provide consumers and business with vanilla services for spending and borrowing/lending. The second will come in the form of a holding company that controls investments in a number of independent firms offering the unbundled variants of banking that fintech is espousing.

As a holding company, these investments within each entity will be as going concerns, with no terminal pressure to exit. This kind of liberation will allow each unit under the umbrella to operate freely within their own cost, technological, and cultural constraints. For the owners of the holding company, they will retain the exposure to a “banking conglomerate” but in a far different manifestation and coexistence of fintech and banks to what we see in current times.