Great Recent Examples of Competitive Strategy Successes

How have Michael Porter's competitive strategy frameworks translated to the digital economy? Three recent case studies are presented and analysed.

This article was originally published on Toptal

The Evolution of Corporate Strategy

Within the realms of the business world, pre-20th-century theories of competitive strategy focused on binary outcomes; mainly how to bludgeon markets with monopolies and exclusivity agreements. As markets became more liberated, compromises and specializations became more important and up to the mid-20th-century teachings moved towards gaining internal proficiency within business analysis.

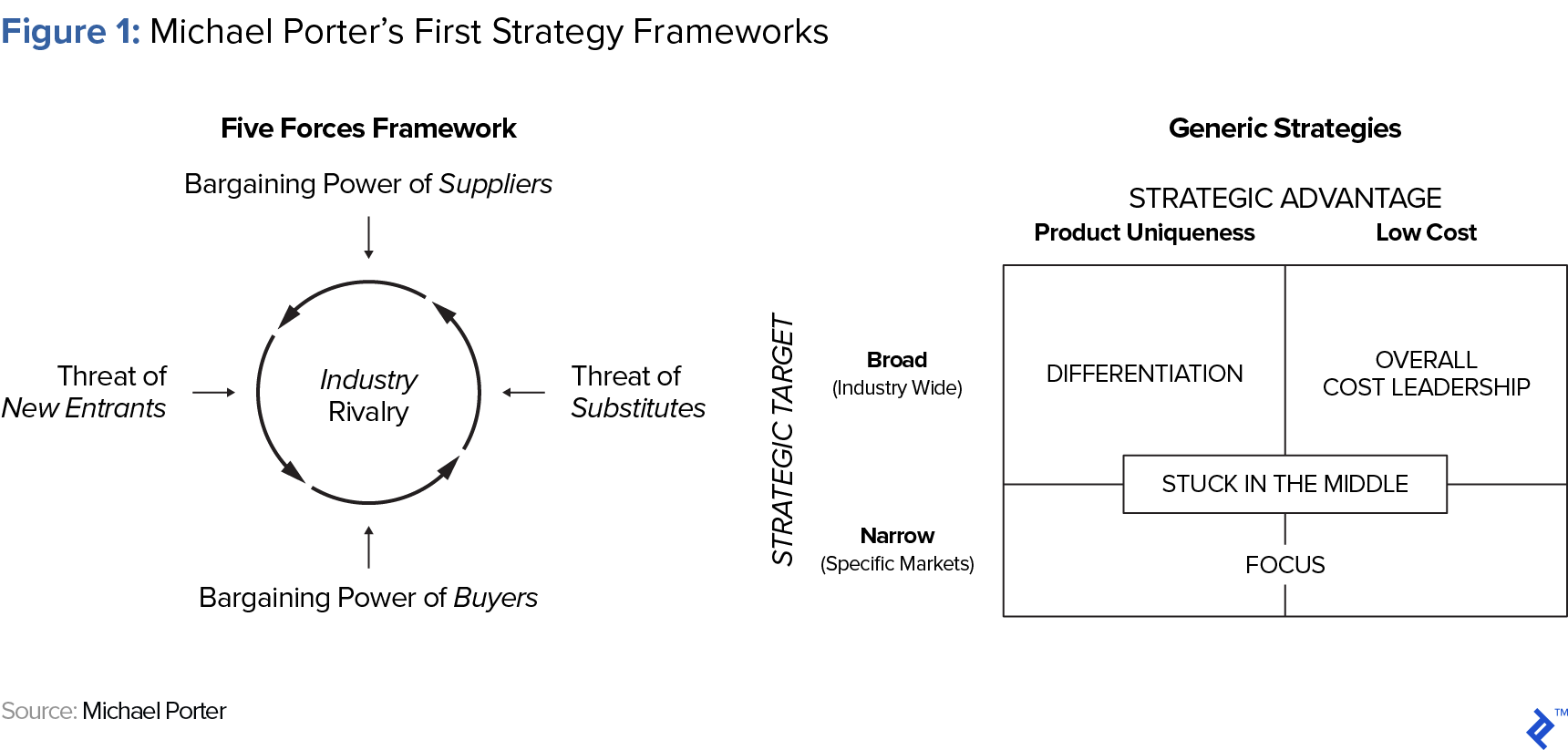

In the late 1970s, competitive business strategy was brought into the mainstream through the publication of Michael Porter’s Five Forces Framework. Offering a competitor analysis tool to assess markets based upon dynamics of the bargaining power of buyers and suppliers, the threat of new entrants and substitutes, and overall industry rivalry. A more in-depth explanation of this method can be read here.

His follow-up was named Competitive Strategy, which introduced the concepts of Generic Strategies. This framework was based on the assertion that in order to maintain above average long term profitability, a firm requires a sustainable competitive advantage. There are two high-level ways that a firm can possess this: through having the lowest costs or via product/service differentiation strategy. A firm must achieve one of those, or the third, a focused specialism of either strategy within targeted markets. If the firm does not focus on one of these, it could stretch itself too thin with contradictory strategy, resulting in it being “stuck in the middle”. The figure below shows a graphical representation of his two seminal strategy frameworks:

Porter’s Generic Strategies inspired countless case studies, recounting the successful types of competitive strategy implemented by businesses such as Walmart, Southwest Airlines and Ikea.

In 1996, Porter wrote “What is Strategy,” which introduced his activity positioning strategies, describing paths that businesses can take in order to gain competitive advantage within value chains. He wrote that there are three activities that can be followed within this positioning framework, variety-based, needs-based, and access-based. As a compliment to the generic strategies, these tactics gave more clear paths towards how a firm can gain competitive advantage and thus, succeed within a wider generic strategy.

For example a cost-leadership generic strategy merely implies that a firm must produce at the cheapest cost. But how does a company reach that point? Porter’s activity strategies complement this work through offering positioning routes. They are shown visually below, followed by their explanation with some competitive strategy examples from successful companies of the era.

1. Variety-based Positioning

This is a strategy wherein a firm produces a subset of an entire industry’s products or services. It thus chooses to not segment itself by the customer, but instead through the choice of offering. This focused approach can allow a company to scale through specialization and, by allocating resources to specific areas that enables it to accelerate innovation, drive better service and achieve lower costs.

Porter used the example of Jiffy Lube for successful variety-based positioning. A business that he cited had succeeded by solely producing automotive lubricants and with no ancillary products, or services offered. This resulted in faster service, cheaper cost, and a superior product

2. Needs-based Positioning

The converse of variety-based positioning is the option of just targeting segments of customers and fulfilling all of their needs. This builds excellence through understanding a customer and capturing its full value-chain through tailored service and repeat business.

The examples provided for this strategy were within the industry of wealth management. Whereby Bessemer Trust and Citibank had gained success by solely targeting clients with investible assets of $5 million and $250 thousand respectively.

3. Access-based Positioning

The final strategy is targeting customers that have similar needs, but with disparate access routes to the product or service. Access can be defined by customer geography or customer scale, insomuch that a firm requires different delivery methods in order to serve them effectively.

Carmike Cinemas (sold in 2016 to AMC Theatres) was provided as an example of a successful application of this strategy. It was a chain of cinemas that targeted small town cinema-goers in rural areas. Operating a central corporate function allowed Carmike to gain economies of scale, yet it distributed the cinema experience through a tailored local service. One such example mentioned was via cinema managers who knew patrons by name and ran their own marketing campaigns.

Modern Examples of Competitive Strategy

When we talk about strategy of digital companies, the conversation is usually framed around concepts of innovation, in particular towards Clayton Christensen’s Disruptive Innovation ideas. Yet once a a business has innovated, it still needs to have strategic planning in place to ensure that it can execute and seize competitive advantage. Apple and Nokia spring to mind for companies that have had their respective strategic successes and failures scrutinized heavily in recent times.

In light of Porter’s competitive strategies being over 20 years old, this article will use his activity mapping framework to demonstrate the advantages of strategic planning via case study examples of success from the digital economy.

Variety-based Positioning: Nvidia

Nvidia is a producer of graphic processing units (GPUs), which at the age of 24 is recording annual revenue growth of 48% and gross margins just shy of 60%. Impressive figures for a mature business.

The GPU was invented by Nvidia in 1999 and, within the vast chip market, it is still the only offering that it produces. If you look on its website, instead of having the standard “Product” section listing its types of hardware, Nvidia shows the “Platforms” that it creates GPUs for. This is particularly pertinent as a successful application of needs-based positioning, as Nvidia’s strength in GPUs is so strong that it has tailored its SKUs exactly to the specifications of its client sets.

The growth of video gaming has helped drive demand for GPUs and hence, the success of Nvidia. Half of its revenue comes from this sector. Such a specialization has not limited Nvidia; instead, as new industries have spawned, they have deviated towards the powerful technology that it creates. Self-driving cars and augmented reality are two such examples of new cases, which Nvidia has adapted towards and now serves. GPUs are now the center of the artificial intelligence universe, which will also be harnessed to help maintain the pace of innovation of GPU processor speed.

The price of GPUs has risen in recent years due to cryptocurrency mining, which favors the most powerful GPUs. In June 2017, one analyst estimated that cryptocurrency mining alone drove $100 million worth of sales to Nvidia in just 11 days. One could call this a strike of luck, or a positive externality of its technology enabling new markets.

As the pioneer of the GPU, Nvidia has built itself into a gatekeeper of the ecosystem, using events like the GPU Technology Conference to bring together stakeholders and keep itself at the center of proceedings.

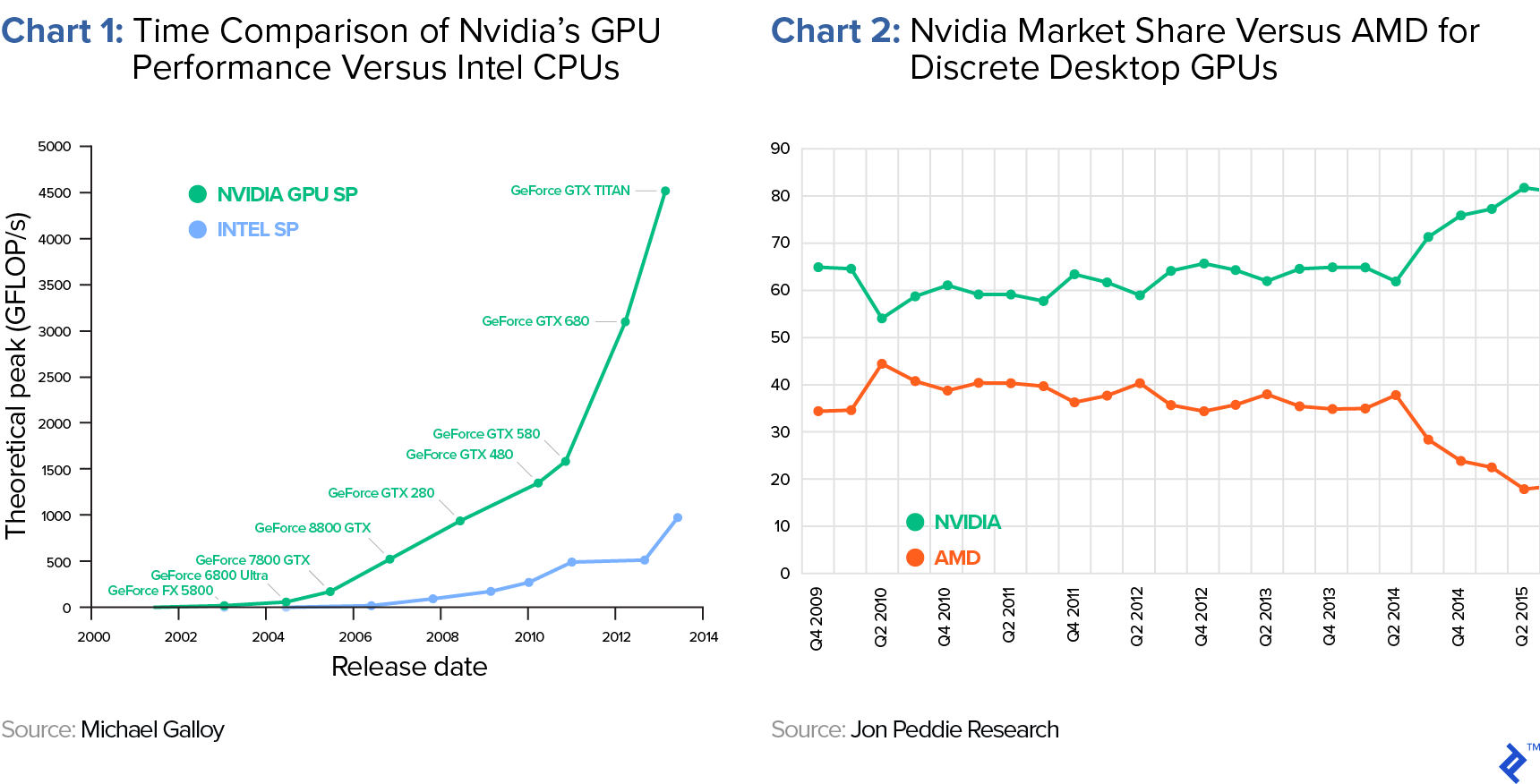

Over time, its efforts in GPU development has helped Nvidia to accelerate performance improvement relative to the incumbent medium of central processing units (CPUs). Through this visual example of Moore’s Law in action, it has also grown its own market share relative to its main competitor, AMD:

Compared to AMD, Nvidia has consistently outperformed it. From a shareholder’s return perspective, it has returned approximately 850% more than AMD over the past four years:

With a 58.8% gross margin, Nvidia outperforms AMD (23.4%) by almost 35%, which is a negative EBITDA business. AMD has been riding the GPU wave too and has comparable output performance from its chips. So why does it have poorer financial performance? Well, AMD is not as focused as Nvidia—it also makes CPUs, where it competes heavily with Intel. It engaged in an ugly, drawn-out lawsuit with Intel over antitrust matters that distracted it during the past decade, in addition to fighting with Nvidia in the high-end GPU market. AMD is overstretched and, hence, earnings have disappointed.

Needs-based Positioning: Pinterest

The golden era of the social network pioneers may be long gone. Despite their continued popularity, Facebook, Twitter, and LinkedIn all emerged over a decade ago. The costs needed to build up a network and attract users are exorbitant and even if they aren’t winner-takes-all markets, it would take a brave business to try. Attention now has diverted towards messaging and interaction. The dominance of Facebook is demonstrated through its purchases of two of the most promising startups that recently emerged from this sector, Instagram and WhatsApp.

One such company that has recently carved out a successful niche within this market is Pinterest. At seven years old, it is still relatively young and largely flies under the radar, yet it is valued at $12.3 billion (the 10th highest valued private tech company). Its network has 200 million monthly active users, half of whom are in the USA and 81% of whom are female. It grew its initial user base through referral tactics, shunning expensive paid-for acquisition methods.

Pinterest has grown within a mature and competitive market through needs-based positioning. It brings value to specific types of users who use the network to discover and buy new things. If you search for Pinterest, this is what you see:

Its photo-based list interface has allowed Pinterest to naturally deviate toward activities that benefit from this, such as sharing interior design and fashion ideas. The user benefits because unlike, say, Amazon’s “Recommended for You” section, these lists are curated by users and bring wider and less biased suggestions.

Having defined psychographics of loyal users and use cases for the network is catnip for marketers. Pinterest could have tried to compete with the wider social networks by being a “jack of all trades, master of none” type. Instead it embraced its core user base and those that drive the most value from image-based lists. This brand strategy has in turn also driven value for the other side of its market, advertisers.

A now deleted-article by the private company showed statistics of its users, showing that 93% of them have used the platform to plan for a purchase and then 52% have then gone on to buy it online. It is the second highest source of referral traffic to Shopify and its average order size of $50 is the highest from all the social networks. It generates 5% of all referral traffic on the web. Research from Mary Meeker’s Internet Trends report in 2016 showed how Pinterest drives strong traffic for internet purchases:

Despite only starting to record revenue from 2015, Pinterest made $100 million in that year, which grew to $300 million in 2016 and could reach $600 million by 2017. SharesPost International estimates that yearly revenue will continue to expand at 40-45% per year up to 2020. Through needs-based positioning, Pinterest has created a lucrative network that services specific users and through that it has found revenue opportunities via referral advertising.

Access-based Positioning: Xoom

I feel that the best example of digital companies that have used effective access-based positioning to build competitive advantages are those in the money transfer industry. Looking at remittances, the traditional process is that senders go to a branded bureau (for example Western Union) and then their recipient picks it up from another bureau in the destination country. Sure, it works, but who benefits the most from this? Western Union of course, who keep users within its ecosystem, regardless of the compromises that users have to make to send or receive.

By eschewing using its own infrastructure and acting as an enabler of transfers, Xoom (established in 2001) gave its customers more choice. Xoom would allow a sender to send via their phone and then the receiver could obtain cash in a number of ways, such as bank transfer, phone top-up, or cash pickup.

By not defining cash pickup to “Xoom bureaus” and instead using third party brands, it increased the options available to customers. This was also lucrative for Xoom as, in the process, it also earned higher gross margins than Western Union, as it did not have to build out any of its own proprietary branch networks.

Xoom shows a great example of building competitive advantage via access-based positioning. Its users have the same needs (send and receive money), but each has nuanced aspects of their needs based on their geography. Cash pickup for an urban recipient can be an easy option to take, but for a rural dweller, the comfort of receiving it via phone credit may far outweigh the inconvenience of a journey to an affiliate cash pickup location.

PayPal eventually bought Xoom in July 2015 at a $890 million valuation, a 32% premium to its share price at the time. Considering that PayPal is a behemoth of money transfer, why would it not just replicate Xoom itself? Well their intentions will have been driven by buying Xoom’s brand value, but also in buying its expertise for earning competitive advantage via access-based positioning. PayPal’s own P2P payments system has shades of Western Union’s, in that for one user to send to another, they both need to have PayPal accounts.

Summary

We are in an amazing era of innovation, with startups and businesses ripping up norms and bringing value to consumers through more choice and utility. However, one reason that many startups ultimately fail is because they follow a mentality of “If you build it, they will come.” This leads to situations where startups get outmaneuvered in their markets by not considering how they can win competitive advantage.

There are now many competitive strategy techniques for analyzing industries and competitors. Within these, Michael Porter’s frameworks provide solid tools for businesses to use for planning their positioning in the market. Despite approaching their 40th birthday, they still hold firm for digital companies to look towards when making business models and compiling competitive intelligence.