Fatigued by the Subscription Business Model

Are too many consumer products businesses trying to stimulate the recurring revenue characteristics of SaaS by offering subscriptions?

This article was originally published on Toptal

Earlier this year, my bank invited me to become a “member” of the credit card that I had been using for a number of years. I was intrigued.

Unfortunately, it was an underwhelming proposition.

The benefits of membership were essentially what I was currently enjoying for free (cashback and no FX markup), yet to be now offered at a charge of ~$10 a month. Reading between the PR, the bank must have undershot borrowing estimates and was now trying to plug the profit hole with the new consumer buzz word: the subscription.

Once a realm of benign staples like milk, or niche hobbies, subscriptions now permeate all kinds of consumer markets. Brands are moving toward formalizing our repeat purchase trends and increasing wallet share. It’s a carbon copy of the proven Software as a Service “SaaS” playbook that was introduced in the early 2000s.

Returning to the case of my credit card, the incident made me wonder if the race to subscriptionize everything has gone too far. It seems that many subscription businesses are misguided attempts at “synthesizing” recurring revenue and loyalty within either commodity or niche product offerings to appease wide-eyed investors.

Have We Reached Peak Subscription?

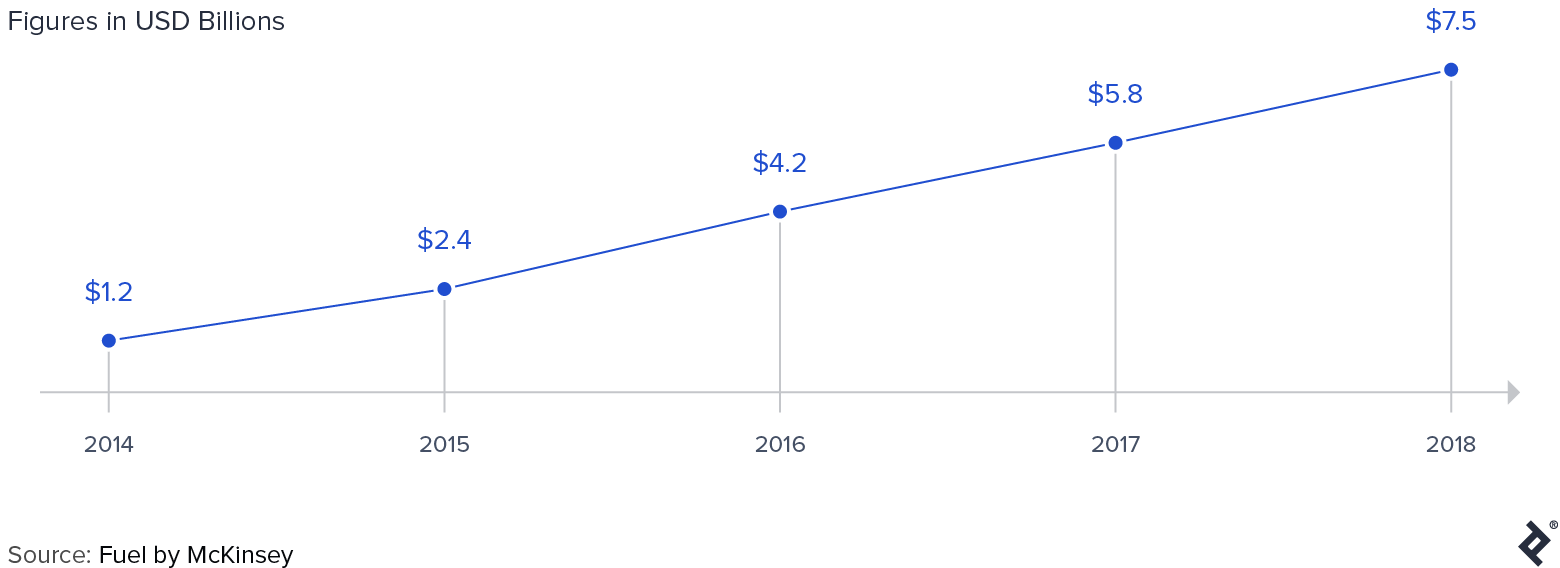

The subscription eCommerce market had sales of $7.5 billion in 2018 and has been growing at 60% on an annualized basis, according to Fuel by McKinsey. Bear in mind that digital subscriptions won’t be included here; Amazon Prime has 150 million subscribers, which would equate to ~$15 billion in annual revenue alone.

Subscription eCommerce Sales $ Billion

The same analysis classifies consumer subscription models into three jobs-to-be-done-esque categories: curation (55% of the sample), replenishment (32%), and access (13%). Curation being the most popular form of subscription is an ironic antidote to the ailment of eCommerce: mass abundance and the value of paying someone to sift through it all.

Subscription revenues are growing because its share of our wallets is increasing, over it being a rapidly increasing overall market. The average consumer’s monthly spend on subscriptions has risen by 141% over two years (£18.49 in 2016 to £44.55 in 2018), according to subscription management platform provider Zuora’s analysis of UK consumers.

Subscription-focused businesses have a high failure rate, with of a given cohort succumbing to defeat, according to My Subscription Addiction. Clues as to why can be inferred from the 40% of customers that eventually cancel subscription plans, with half churning inside the first six months alone. The seemingly homogenous nature of trying to sell everyday things on a subscription that we used to just go to the shops for – funded with steep marketing costs and discounting – does draw parallels with the flash-sales craze from a decade ago.

The fine line between success and failure in the subscription-based business model also seems haphazard. Take HelloFresh and Blue Apron, two seemingly identical meal kit businesses that both went public in 2017, each at valuations a shade below $2 billion. Since then, Blue Apron has floundered; it is now worth just $47.4 million and is on the brink of bankruptcy. On the other hand, HelloFresh has, to all extents, thrived.

There will be a lesson of better execution to be learned here, but the overriding message hints at being one of hubris and shoehorning. It turns out that meal kits were not a particularly revolutionary form of consumption after all.

Shoehorning in a Subscription

In global eCommerce markets with cloud-based drop shipping operations available at the click of a button, ideas can be put to work extremely quickly. Such ease means that it also becomes very difficult to defend brands and ideas when competitors seemingly materialize at multiplicitous rates. This can be particularly disheartening and terminal for pioneers in a field, who act as Trojan horses by building up hype for a new market (through hard marketing dollars), before a glut of new entrants arrive and force down prices.

Businesses that see customer lifetime value figures shrink from the race to commoditization will think of creative ways to address the slide, with subscription plays often seen as a silver bullet. However, unlike the razor blade, or games console business models from the past (sell the “base” at cost then earn margin on the “disposables”), these subscription plays often seem shoehorned in and tenuously linked to the original product:

- Clear Teeth Aligners. Since Invisalign’s patent expired, prices for at-home clear teledentistry have halved due to their disintermediation of orthodontists. Many D2C startups offering such products now try to offer teeth whitening as a recurring revenue shoehorn into this rapidly commoditizing industry.

- Mattresses. The discovery of vacuum packing a mattress into a box was a noble, yet moat-less innovation. So many businesses now offer such products that a WSJ reporter tallied that up to eight years of free sleep could be obtained through gaming free trial periods.

- Juicero. When a juice press can raise $120 million of fundraising, it becomes inevitable that merely selling a $400 device will not suffice…

The SaaSification of Everything

SaaS was a revolutionary subscription business model in enterprise and B2B software markets because it established bonds of mutual benefit between consumer and vendor. For IT procurement managers, the threat of obsoletion was removed, and hardware costs became outsourced into the cloud. The vendor itself could pick up traction quickly with a self-service sales model relieved from the arduous sales cycles of traditional pitches.

Software implementation costs were effectively converted from large upfront payments into perpetual annuities. This was less risky and more scalable for enterprise customers, and, for the developer, once initial software development costs were repaid, they entered zero marginal cost, “flywheel” territory, with the power and clout to try new things. Look at Salesforce, one of the godfathers of SaaS, it’s now a $200 billion juggernaut with all kinds of activities unrelated to its first initial product, a straightforward CRM system.

That’s all well and good in B2B/enterprise markets, but the problem I see with consumer goods companies clambering to enter the SaaS-type subscription business model is that:

- Most of the subscriptions are just dressed-up forms of trade financing.

- Business models are being planned to suit investors’ desires for SaaS-type characteristics of recurring revenue.

- The lack of iterative improvement to the service and weak defensibility from competitors means loyalty is far harder to earn.

The Allure and Fallacy of Recurring Revenue

The allure of the subscription for businesses is the goal of attracting recurring revenue because this accretes to an increased overall customer lifetime value. A subscription becomes a very “direct” way of formalizing repeat purchase loyalty because it diarizes charging customers’ bank accounts each month.

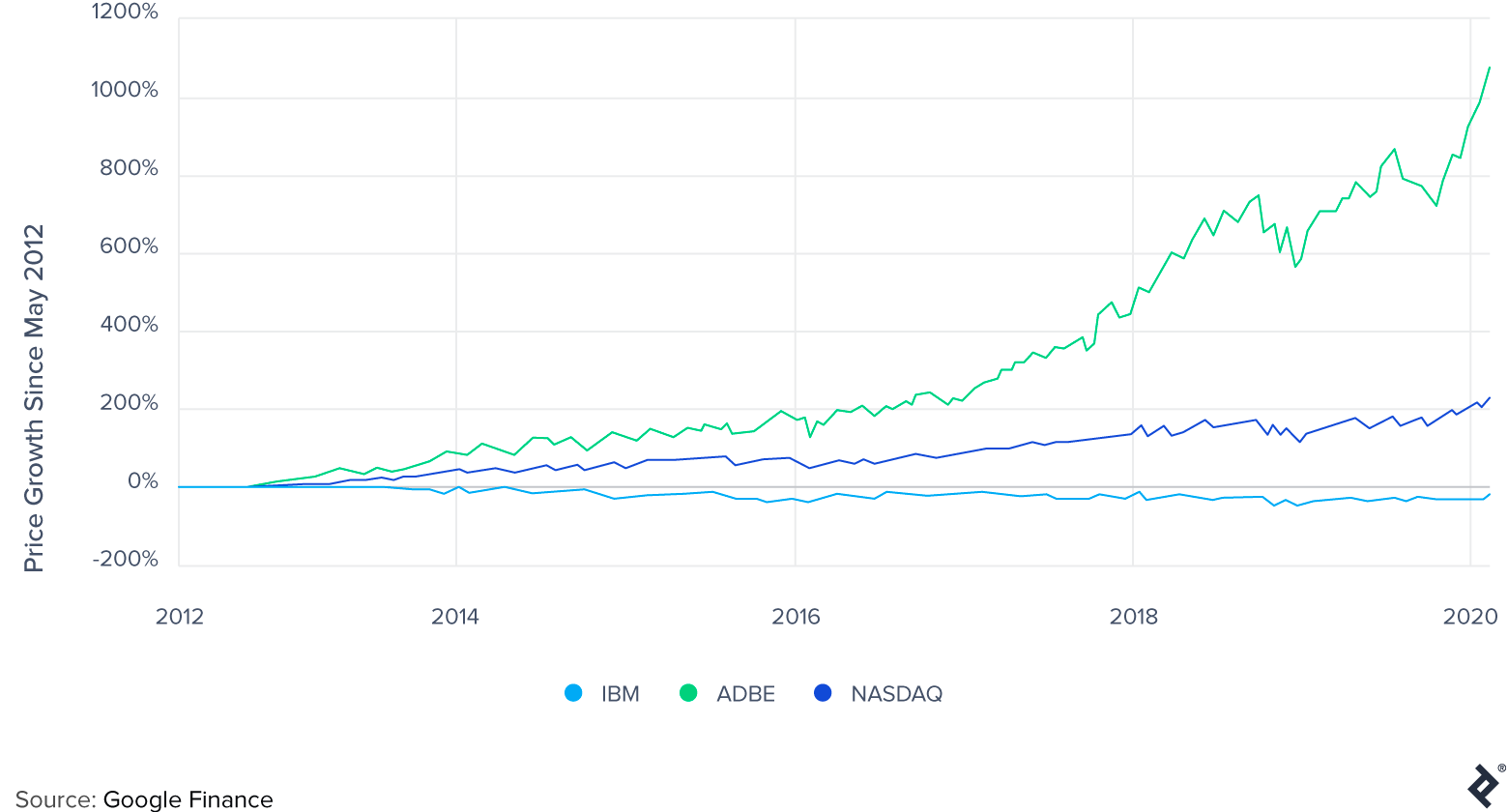

The promise of the subscription is driven by the goal of attracting sticky revenue, which in the case of SaaS businesses has given them historical valuation upticks of 2-3.5x more than an equivalent one-off license pricing competitors. Adobe, for example, in the years since it introduced subscription pricing in May 2012, has seen its share price increase by more than 1,000%, far more than the NASDAQ’s 200% rise. For even more context, over the same period, IBM – which has struggled in the cloud era – fell in value by 25%.

With SaaS and digital subscriptions, recurring revenue allows for further product improvements, which further embeds incumbent customer loyalty. Developers have live access to user behavior and can see what works and what doesn’t. When something is clearly delighting consumers, it becomes a no-brainer to allocate more resources (the recurring revenue) into enhancing it further. Remember how Netflix made Bird Box based on user viewing patterns?

For physical product subscriptions, more often than not, the recurring revenue will not go into such value-accretive activities:

- How can you innovate or improve on a meal kit that arrives on a doorstep each week?

- How do the data-moats that enrich digital users’ experiences by learning more about them over time manifest within physical goods markets?

The answer is that, more often than not, they do not.

Many subscription businesses fall into the trap of using the subscription as a trade financing vehicle—frontloading revenue in order to spend it all on marketing to more expensive-to-acquire new customers. Recurring revenue in such cases will only equate to loyalty if the status quo remains static and apathy prevails.

Earn the Repeat Purchase

The notion that you need subscriptions to learn more about your customer can again be debunked by other markets’ history. Take banking, the ultimate industry for requiring sticky and recurring features (in this case, from deposits). While perpetual notice accounts are prevalent, the vast majority of deposit money either sits on fixed-term accounts or on call in checking accounts. These two extremes are not contractually recurring, yet banks will model up trends and stress test rollover percentages (essentially churn) in its risks teams in order to ensure ongoing solvency is assured.

For generations, consumer goods companies have coped without requiring subscription business models. The FMCG giants that stock households did not encumber consumers with clunky subscriptions. Instead, that dynamic friction of “earning” the repeat purchase maintained trust between brand and end user. Brands would tally up monthly order histories to derive seasonal trends and use coupon/survey promos to go direct to end consumers to learn more about feedback and habits.

Conditions Where Subscription Business Models Work

In the past, the subscription brought physical convenience: the local rag delivered without the need to pop out in the rain, the fresh milk on your doorstep before you wake up. The digital economy has raised the stakes for the value-add element of a subscription. For these two nostalgic examples—the magazine can now be read digitally, and eCommerce discovery makes it easier to find a better-suited milk vendor.

In 2020, though, I see the following factors as being important to consider within the context of a subscription business model.

1. Psychology

Looking into some widely regarded traits of what subscriptions serve, you can divide them into two psychographic traits: what we need (necessities) and what we want (luxuries).

A good subscription business model excels in one of those areas but has more long-term defensibility if it can find something inside the intersection between the two. In terms of necessities, that will ensure differentiation from a pure commodity offering, and in terms of luxury, it extends the market beyond just for a niche “nice to have” service.

Here are some examples:

2. A Trust Bond

With SaaS, the customer relies on the vendor to continually support software, or else they will churn. This dynamic maintains a healthy relationship between both parties, with aligned incentives.

Can you say that the same is true for most consumer-facing subscription businesses? It’s definitely more tenuous to think that you can have continuous product improvement and innovation cycles with benign consumer staples.

Instead, more often than not, a subscription is used to capitalize upon apathy. Unlike a SaaS product where usage is a benefit to the vendor because it provides them with first-hand feedback about what is useful and what is not, at times, consumer subscription businesses benefit most when consumers don’t use the service. Profiting from apathy is not an ideal long-term business model.

Having a social impact element to the business can help convey better a trust bond. In the UK, there are businesses that offer boxes of “wonky” vegetables that don’t fit supermarkets’ desired aesthetic for the perfect carrot. Not only do more customers enable the business to reach more farmers, but more customers also empower the company to reduce food waste.

3. Buffet-like Sensations

The reason all-you-can-eat buffets exist is because they actually make money. They feed off an irrational greed that the consumer thinks they will get more utility than the other diners by consuming more. Yet, over the course of time, the buffet will still turn a profit.

Consumer subscriptions work when there is some element of this buffet mentality. If an all-you-can-eat subscription brings utility and satisfaction to the user, their evangelizing of the service will then attract more diners.

Take Spotify—a song gets on average $0.0072 in royalties per play (based on the average of the previously disclosed range of $0.006 to $0.0084). The service costs $9.99 per month, meaning that 1,388 songs are “included” in the price. To listen to 1,388 four-minute songs, a user would need to spend 92.5 hours a month on the service, or just over three hours per day. Based on this, I can put my hand up and say that Spotify is making money from me, but I also think it’s a great value service, even though I don’t get my “maximum utility” from it.

I believe it is this element that separates the trade-finance subscription businesses from the ones that will stand the test of time. The key reason why consumer product subscriptions are so hard to get right is because it’s quite difficult to get that “all you can eat” mentality in an analog context. Some examples of those that do:

- ClassPass: While not “unlimited,” the bundled pricing of gym classes is an attractive proposition to users.

- Amazon Prime: Mastered the free delivery hook, which then encourages shoppers to buy more.

- Unlimited data cell plans: Eventually, users are throttled if they use too much data.

What’s the Next Craze?

Building a business to appease investors that you one day hope to attract is a dangerous path in the evolving journey of business-building gamification. Following the SaaS gameplan of demonstrating recurring revenue metrics was one way that this transpired. Now, in 2020, in the post-WeWorkian aftermath of chasing profits over growth-at-any-cost hyperscaling, the bar has been set even higher for consumer goods startups.

The macro environment for consumer eCommerce is extremely tough. The omnipresence of large aggregators like Google, Facebook, and Amazon serve as gatekeepers to the market, charging their advertising tax and owning customer relationships. These conditions force many consumer goods companies into a race to the bottom on pricing and differentiation.

The Rise of the Rundle

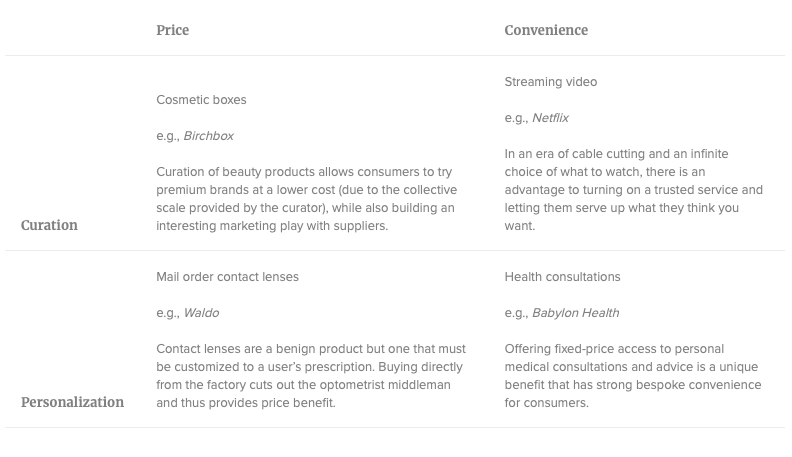

Such aggregation can cause the necessities of “price” and “convenience” to quickly converge into easily replicated commodities. We see large tech behemoths now capitalize upon convenience by building up recurring revenue bundles - rundles- subscription offerings, making them a one-stop-shop for consumers to go to. Think how Apple went from Apple Care into Cloud, News, Music, TV, and Games within just a couple of years. All this extra revenue and attention gives them a flywheel of momentum to try ever more audacious feats, like taking on Hollywood and Detroit simultaneously.

Therefore, I expect the next wave of consumer startups to focus on the curation and personalization aspects of recurring revenue products that are harder to clone and are more bespoke by nature. Subscriptions succeed when they find ways of bringing incremental value to consumers over time. Someone smart will one day figure out how to do this in a scalable manner for consumer products.

It’s tough for new brands to find organic customers online. For that, I also think that an old-school, offline element of hyperlocal marketing will become de rigueur. Finding customers in their daily lives, then moving on to serve them online, outside the mass-market aggregator ecosystems, might be the most viable way forward.